Dead Aunt in Suitcase: Why This Case Raises More Questions Than Answers

Dead Aunt in Suitcase: Why This Case Raises More Questions Than Answers

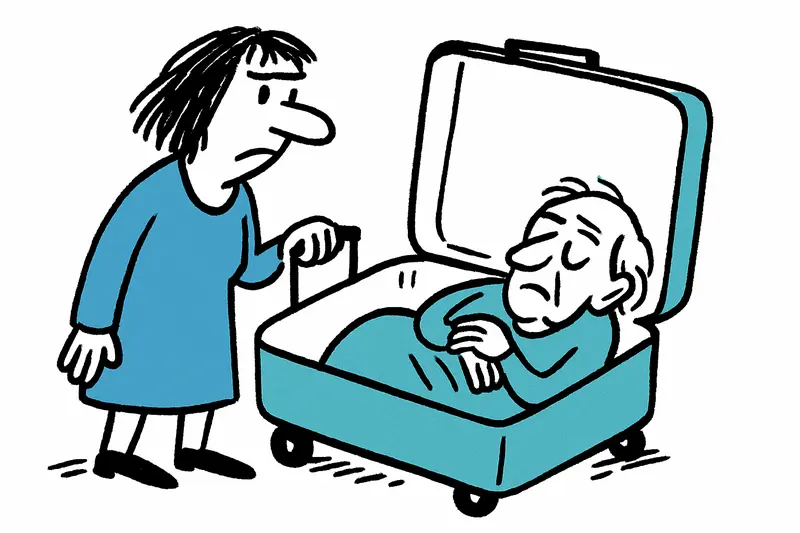

A court sentenced a woman to 17 years in prison after she confessed to killing her 91-year-old aunt in Sineu and transporting the body in a suitcase to Palma. How could the situation escalate like this — and what is lacking in the protection of elderly people on the island?

Dead Aunt in Suitcase: Why This Case Raises More Questions Than Answers

Key question: How can a care situation spiral to the point that a relative dies and the body is taken in a suitcase to another city?

The court ruling is on the table: 17 years in prison for Antonia S.G., who is said to have killed her 91-year-old aunt in Sineu in mid-April 2024. The woman confessed, so there was no jury trial. According to the indictment, she had taken the senior into her care a few days earlier because the woman was experiencing a "progressive cognitive decline". Investigators report severe blows, broken nasal bones, pressure on the chest resulting in broken ribs, and a stab wound to the chest. Afterwards the defendant is said to have tried to cover up the act: cleaning the scene, hiding the body in a suitcase and transporting it to Palma, where emergency services and police later became suspicious.

In short: a brutal isolated case that caused a lot of attention on the island, similar to other local discoveries such as Fatal Discovery in Son Macià: A Case Raising Questions about Protecting Older People.

First: care is often a family matter. In small towns like Sineu people know each other, see neighbors on the plaza, hear the church bells and assume the family will take care. When an older person with cognitive problems suddenly moves in with a relative, this is often not automatically accompanied by professional services. Why was there no prompt check by social services, no visit by a qualified care nurse? In many cases staff and resources for regular home visits are lacking, especially outside Palma, a gap highlighted by reports such as Body Found in Santa Catalina: When an Entire Neighborhood Didn't Notice.

Second: prevention and training. Relatives often take on care tasks without sufficient preparation. No training for aggressive behaviors in dementia, no respite offers, no clear contact point for overload. That creates fertile ground for overwhelm, hidden aggression and in the worst case violence. The fact that an emergency number ("061") was called suggests the defendant also sought help—or at least tried to justify the situation. Emergency crews became suspicious; that shows that responders can notice something when they arrive. But how often does such a suspicion not lead to further investigation?

Third: the judicial process. Because the defendant confessed, further evidence was not heard before a jury. For the victim that may no longer matter; for society it does: a comprehensive public trial might have shed more light on the circumstances—how care was organized, who had been informed, whether there were earlier signs.

What is missing so far from the public debate: an honest discussion about how we as a community deal with demographic change. It is not only about sentences but about structures that prevent violence. We often talk about beds in nursing homes or the costs of care, but rarely about preventive home visits, respite for caregiving relatives in small communities or concrete alarm chains in cases of suspected abuse.

An everyday scene that makes the problem tangible: on a cool morning on Calle Major in Sineu an older woman sits with knitting on a bench. A delivery van honks, the baker sweeps in front of his door, children run to school. No one loudly asks whether the woman is alone in the evening, as other incidents such as Santa Catalina: Man reportedly lived for a month with his dead mother – questions for the city have shown. It is precisely this invisible loneliness combined with a lack of professional support that creates the space in which overwhelm can turn into danger.

Concrete solutions can be derived from these observations: First, expand mobile social and care visits in the villages, financially supported by the island administration. Second, low-threshold training offers for relatives—courses on behaviors in dementia, de-escalation and managing one's own stress. Third, a binding reporting chain: if emergency services suspect abuse at an emergency, social services should automatically be informed and act quickly. Fourth, temporary respite places (day care or short-term care) also in smaller communities so that caregivers do not remain without a break.

These proposals are not revolutionary. They cost money and require political priority. But they are not aimed solely at punishment but at prevention. A sentence can punish an individual case; only better structures prevent such individual cases from becoming more frequent.

Conclusion: The sentence—17 years in prison—answers the question of criminal responsibility. Harder is the question of how an island society protects its older, vulnerable members and at the same time prevents relatives from ending up in situations that end in catastrophe. If we really want to learn something from the case of the murdered 91-year-old, we must start in the quiet places: with home visits, respite offerings and support for the people who provide care.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

Winter Sun: Five Quiet Coves on Mallorca That Are Especially Enchanting Now

Winter sand, a calm sea and faint scents of pine: we present five coves — from easy-to-reach to adventurous — for relaxe...

Adrián Quetglas: Good Cuisine for Many — a Visit on the Passeig

A walk to Passeig de Mallorca 20 leads into Adrián Quetglas's small universe: award‑worthy lunchtime menus, creative pla...

It cracks, creaks, rattles: Reality check on the storm warning in Mallorca

AEMET issues a yellow storm warning with gusts up to 100 km/h in the Tramuntana and waves up to 3 meters. A critical ana...

Portocolom gears up: Fishermen's huts and quay receive new protection

Craftsmen, boats and the salty smell of the harbor: this winter Portocolom is seeing extensive work on the promenade and...

Felanitx: Between the Plaça, the Park and Renewal – the village that likes to carry on

Felanitx presents itself as a place of familiarity and small innovations: market vendors, a meeting spot at Ca n’Usola, ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca